Some time ago I wrote a series about Algebraic effects. I explained then that you could either explain the topic using Math concepts (Denotational) or by showing how it works under some runtime environment like JavaScript (Operational). I choose the second way because I felt it would’ve been more approachable to programmers, and also because I didn’t have myself enough understanding of the Mathematical theory behind them.

I think there is a simple way to put the denotational explanation without brining in the heavy math formalism. IMO this alternative view is better and simpler than the four lengthy posts I wrote back then. It also explains what Algebra has to do with side effects in programming.

Algebras

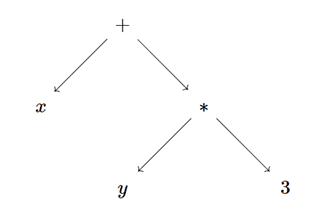

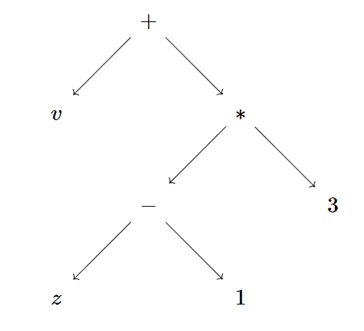

Let’s start from simple algebraic expressions like x + 2, x + (y * 3) … We construct such expressions by combining variables and constants using operations like + or *. We can envision those expressions as trees branching at each operation, with variables and constants at the leaves.

To evaluate an expression, we need to assign values for the variables. In a program, we could have a function evaluate(bindings, expr) which computes the value of expr, given an object that binds each variable in the expression to a concrete number.

But we could go a little further and allow bindings to assign other sub-expressions to variables. For example, evaluating x + (y * 3) with a binding like { x : v, y: z - 1} would substitute all occurrences of x and y to produce v + ((z - 1) * 3). Visually, it’ll look like we grew the tree by inserting new sub-expressions at the leaves

Specification

Mathematicians have a nasty obsession for abstractions. For instance, instead of talking about adding 2 integers, they would abstract away some common properties, like the fact that addition is associative (x + (y + z) = (x + y) + z) and then define a sort of abstract interface (for associativity, they call it a Semigroup). Any Set with an operation that satisfies the above equation could be considered an instance of that interface.

There is a whole catalogue of those abstract interfaces, or Algebraic structures as they are called, that are studied in the field of Abstract Algebra. But we’re not interested in them. What’s important to us is, like the separation interface/class, we distill the process: first we define of a bunch of abstract operations in terms of some equations that must be satisfied, and then pick a concrete Set, then define some functions on that Set that implement the specified operations in a way that satisfies the required equations.

The abstract operations and their ‘equational laws’ can be grouped together under what’s called an Algebraic Theory, that’s the interface. A concrete Set together with functions that interpret all operations is called a Model for the specific Algebraic Theory, that’s the implementation. As you might expect, there is also a special name for the concrete Set used by the Model: it’s called the Carrier of the Model.

For example, we can describe the theory of a Monoid through 2 operations, zero and add (To keep things simple, we occult equational laws).

interface Monoid<A> {

zero(): A

add(left: A, right: A): A

}Then define a Model using the Set of numbers as carrier (we abuse here by equating Sets with Types)

const MNum: Monoid<number> = {

zero: () => 0,

add(left: number, right: number): number {

return left + right

},

}Similarly we can use strings as carrier

const MString: Monoid<string> = {

zero: () => "",

add(left: string, right: string): string {

return left + right

},

}Construction

One thing you will not find in the interface/class analogy is that there is a systematic way to construct an implementation for each interface (i.e. a Model for each Algebraic Theory). It’s really simple, pick any Set, then for each operation, just take the given information as is and keep it.

For instance instead of interpreting the expression 2 + 3 as 5 (losing the initial information about 2 and 3 in the process), we can construct an expression tree (with integers in the leaves) as our Model. Think of it as constructing an Abstract Syntax Tree (We should also consider trees that are considered identical under equational laws as one but that’s not important for us).

And yes, those trees have also got a special name, they are called Free Models.

For example, to construct a Free Model for Monoids over given Set A, we could write someting like

// we'll use a label `pure` to inject values in the leaves

type MTree<A> =

| { tag: "pure"; value: A }

| { tag: "zero" }

| { tag: "add"; left: MTree<A>; right: MTree<A> }

function pure<A>(value: A): MTree<A> {

return { tag: "pure", value }

}

function zero<A>(): MTree<A> {

return { tag: "zero" }

}

function add<A>(left: MTree<A>, right: MTree<A>): MTree<A> {

return { tag: "add", left, right }

}

// No evaluation, just collecting information

let expr = add(pure(10), add(pure(100), zero()))Evaluation

To evaluate expression trees, we can write a function that goes recursively over the tree. But Math allows us to do better, a general purpose function that constructs a tree evaluator from any given Model.

function fold<A>(model: Monoid<A>) {

return function evaluate(tree: MTree<A>): A {

if (tree.tag === "pure") return tree.value

if (tree.tag === "zero") return model.zero()

else return model.add(evaluate(tree.left), evaluate(tree.right))

}

}

const interpreter = fold({

zero: () => 0,

add(left: number, right: number): number {

return left + right

},

})

console.log("result", interpreter(expr))Observe how we’ve abstracted away recursion from the Model and encapsulated it inside fold. Thr Model had only to provide a shallow interpreter for the operations. We’ll see a similar behavior when talking about Effect Handlers (There’s more to say about this actually, evaluate is guaranteed to exist because of the mathematical properties of Free Models, but that’s story for another day).

In fact fold is very similar to the reduce method of JavaScript arrays. If you think of ‘Array’ as an Algebraic Theory with a pair of operations [] and [head, ...tail], then a Model has to provide 2 functions: the first simply selects an element for the case of [] (the second paramater of reduce), and the second combines head and tail (the first parameter of reduce). Semantically, a (well behaved) reduce acts like a fold specialized to arrays.

Programs

There are various mental models to envision a program. The most common is to imagine a series of successive steps. In this model, the program invokes commands that gets interpreted by some machine. After each command, the machine would transition from a state to another. We can charachterize this point of view as imperative, and it’s often made formal by computer scientists using some sort of state machine.

But there is also a declarative point of view, we can imagine a program as one big expression. The expression is handed as a tree to an interpreter that then chooses a suitable evlaluation for the operations.

One could object that the above could only work in the case of simple mathematical expressions, or using the programming language jargon, in the case of pure expressions. How would things like console.log or fetch look like in a tree?

More generally, the question is: how do we get a tree-like representation of side effects. And since we saw earlier that our trees are just Free Models of Algebraic Theories, the question translates to: could we have an algebraic representation of side effects?

We saw that algebraic expressions are constructed by operations that combine other subexpressions. Let’s observe that every operation can take a fixed number of arguments. Common arithmetic operations like + or * are generally binary (taking 2 arguments). In -3 we can view - as a unary operation (taking a single argument). The number of arguments an operation takes is called its arity.

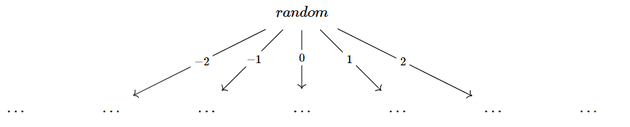

In order to fit side effects in this picture, we need to adopt a wider view of the concept of arity. Let’s take for example the side effect of getting a random value from the environement (like Math.random() in JavaScript). The imperative view envision the side effect as an action which would modify the external world then returns a value. The program would then continue in the new version of the world.

But we could represent the effect with a random operation, but this time with a kind of an infinite arity. For example, say random returns only arbitrary integers, then the arity would be the number of all integers. Visually we’ll have a tree with the random operation at its root, and a branch for each possible answer that can be returned by the operation

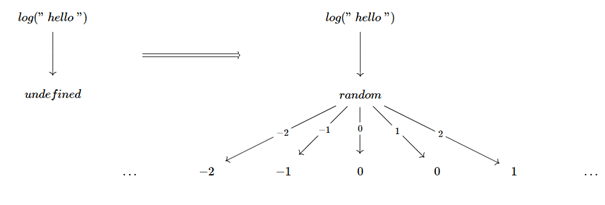

Another example console.log can be seen as a function taking the message to log and returning a (parameterized) log operation. What’s its arity? think about it this way: in the case random there could be, potentially, as many ways to continue the program as there are possible answer values. But sincelog returns a unique meaningless value (e.g. undefined) then there could be only one way to continue the program (simply the code after console.log).

One more example, throw could be seen as a function taking the error to be thrown and returning an abort operation. How many ways are there for the program to continue after abort? None! It’s a dead end, so the arity of abort is 0 (of course the program could possibly continue with an exception handler, but that’s the other side of the story).

we need one last generalisation of the arity concept. For instance, in order to represent the random program above in code, we’d have to provide an argument for each possible answer, something like

random(...[child for -1], [child for 0], [child for 1], ...)But we don’t have enough time or space for it. Fortunately there is a more compact formulation

random(n => {

// return children depending on `n`

// ...

})In this setting, a function acts like a big tuple whith a value for each possible answer expected from the operation. More formally, if integer is the type of integer expressions in our programming language, then we would say that random has an arity of integer. Observe also that the equivalence extends to finite arities as well. A binary operation add(x,y) can also be written as add(b => b ? x : y) and we can as well say that add has a boolean arity.

There is nothing fancy here. From a programming point of view, the function passed to the operation is just a continuation that takes the answer from the performed operation and returns the rest of the program. It turns out that the continuation is a general representation for tuples of any arity.

Just as we did with Monoids, we can use an interface each time we want to represent an Algebraic Theory. This would work well provided we have a sufficiently powerful type system to track side effects. We can also use a generic operation object to represent all possible operations in a program.

More specifically, a program can be either

- A pure value that doesn’t perform any operation or side effect (a leaf)

- An Operation together with a continuation that specifies the rest of the program (a subtree)

In typescript this would be something like (we could perhaps do safer than any but I’ll keep things simple)

type Program<A> =

| { tag: "pure"; value: A }

| {

tag: "operation"

name: string

params: Array<any>

resume: (x: any) => Program<A>

}

function pure<A>(value: A): Program<A> {

return { tag: "pure", value }

}

function operation<A>(

name: string,

params: any[] = [],

resume: (x: any) => Program<A> = pure

): Program<A> {

return { tag: "operation", name, params, resume }

}For example

const random = operation<number>("random")

// { tag: "operation", name: "random", params: [], resume: pure }

function log(message: string): Program<undefined> {

return operation("log", [message])

}

log("hello")

// { tag: "operation", name: "log", params: ["hello"], resume: pure }Obviously we can’t write entire programs in a single hard-coded giant expression tree. Observe that the resume parameter already defaults to the pure function, which means that by default the program performs the operation then returns the answer provided by the external environment.

The default pure continuation allows us to create small truncated programs. what we need is a way to assemble bigger programs (trees) from smaller programs (subtrees). We can acheive this by exploiting the binding operation we saw earlier with simple math expressions. Binding will allow us to extend the program tree by replacing leaves (i.e. pure values) with further subtrees (rest of the program).

function bind<A, B>(

program: Program<A>,

then: (a: A) => Program<B>

): Program<B> {

if (program.tag === "pure") return then(program.value)

else {

let { name, params, resume } = program

return operation(name, params, a => bind(resume(a), then))

}

}bind takes a program and a continuation. If the program is a leaf/pure value, we apply the contiuation immediately to get the rest of the program. This corresponds to ‘substitute a leaf with a subtree’ case. Otherwise we need to call bind recursively on all subtrees (in a => bind(resume(a), then), think of resume as a big tuple: Each entry resume(a) in the tuple is replaced by bind(resume(a), then)).

For example, going from log("hello") to bind(log("hello"), _ => random) could be visually represented as

One more caveat is that writing programs using nested binds is akin to writing in continuation passing style, which is tedious and impractical.

First, let me clarify that the above implementation is just intented as a pedagogical tool. A real implementation of Algebraic Effects would typically be backed in by a programming language, not only to provide an ergonomic way for writing programs, but also to generate an efficient executable.

We still would like to see how our tree representation maps to a traditional code written in a seqeuntial way. In the case of JavaScript, we can use Generator functions to create and bind programs using the sequential style. So for example one would write

function* fetchData() {

let user = yield fetchUser

let repos = yield fetchRepos

return { user, repos }

}instead of

bind(fetchUser, user => {

return bind(fetchRepos, repos => {

return { user, repos }

})

})Below a simple (and ineffecient) implementation for transforming Generator functions into bind expressions, I won’t be commenting the code because the post is already getting long. The code supports resuming the bind continuation multiple times (which means the computation can take many paths in the tree).

function go(gf, args = [], history = []) {

let gen = gf(...args)

let res = history.reduce((_, x) => gen.next(x), gen.next())

if (res.done) return res.value

else {

return bind(res.value, x => go(gf, args, history.concat(x)))

}

}

const program = go(fetchData)

// // { tag: "operation", name: "fetchUser", params: [], resume: ... }We’ve talked about construction, but what about evaluation? That where Handlers fit in the story. Handlers are typically presented as a generalisation of exception handlers that can resume the program from the point that threw the exception.

In our declarative representation, a Handler is just another expression evaluator, like the one we saw earlier for Monoids.

Let’s recall how we implemented the interpreter for our earlier Monoid theory. Given any Model for the Monoid theory, fold generates an interpreter for a monoid tree (the free model)

function fold<A>(model: Monoid<A>) {

return function evaluate(tree: MTree<A>): A {

if (tree.tag === "pure") return tree.value

if (tree.tag === "zero") return model.zero()

else return model.add(evaluate(tree.left), evaluate(tree.right))

}

}

const interpreter = fold({

zero: () => 0,

add(left: number, right: number): number {

return left + right

},

})fold first handles the pure case by returning the pure value (i.e. carrier value). Then for each operation, we start by recursively evaluating its children, then we use the model to recombine the computed values.

Our programs are just expressions with a general notion of arity for the operations. So we can take the same implementation and adapt it.

function handler(model) {

return function evaluate<A, B>(program: Program<A>): Program<B> {

if (program.tag === "pure")

return model.return ? model.return(program.value) : program

else {

let { name, params, resume } = program

if (name in model) {

return model[name](...params.concat(a => evaluate(resume(a))))

} else {

return operation(name, params, a => evaluate(resume(a)))

}

}

}

}The key thing here is the signature of the returned evaluator. It’s a transformation between computations: take a program in, and returns another program out. The returned program could be always a pure value, which means that all effects are discharged. The Model could also handles the effects by performing other effects (or even the same one raised by the input program).

In our new interface, we’re dealing with generic operations, so we need to pass the operation’s parameters to the model. The model gets also a continuation representing the rest of the program (or the operation’s children). Just like fold, handler calls the evaluator recursively on the operations’s children (all a => evaluate(resume(a)) calls).

If our model doesn’t handle the current operation, then we bubble it up to upstream handlers. But in the meantime, the handler wraps itself around the operation. In the tree language, the model just ignores the operation node and tries to evaluate all its children instead.

Finally, we allow the model to preprocess the return value of the program (the leaves) using a special method return. This is needed to allow the handler to change the return value of a program (like a handler for a program performing state effects can return stateful functions state -> [value, state]. [Well, there is also more to this story. The Math formalism requires that the output program, which is also a Free Model, be also a Model for the Algebraic Theory implemented by the input program]).

To highlight the analogy, here’s a reimplementation of Monoids using the new generic interface

function zero() {

return operation("zero")

}

function add(left, right) {

return operation("add", [], b => (b ? left : right))

}

const interpreter = handler({

zero: () => 0,

add(resume) {

return resume(true) + resume(false)

},

})zero is a nullary operation, just like the earlier abort example. The case of add is more interesting, it calls its continuation twice in order to reach both children. Like in the former implementation, the handler doesn’t bother with recursion and performs the addition directly on the results of resume, the recursion is taken care by handler.

A key thing I’d like to emphasize: even if a programming language makes calling operations look like simple function invocations, it’s not the same. The distinction between pure values and effectful ones (often called computations) is core to the theory behind Algebraic Effects. In fact it’s core to any modeling of computational effects, including Monads (If it were not, we wouldn’t need fancy theories about side effects, simple mathematical functions would’ve been sufficient). What makes Algebraic Effects interesting (among other things) is that functions are typically polymorphic over Effects so one for example wouldn’t need a special mapM function like with Monads.

By the way, if you have smelled the Monad in the above code, it’s because our programs are rightly instances of a Monad (It’s much more flexible than the usual Monads and so called the Freer Monad). You could also apply the Tree intuition in the case of Monads as well.

There’s more to be said like the relation between Algebraic Theories and Monads, maybe for a future post. In the meantime, I hope the post gave you a better intuition on the relation between Algebra and side effects.